The U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has released an indoor air quality app for Android and iPhone that addresses indoor air quality (IAQ) issues in schools. The IAQ App can be obtained for free by school administrators from EPA’s website.

It provides resources and checklists for school administrators concerned about air quality in their schools. The app is an extremely thorough tool to help guide school administrators in addressing IAQ issues, but has one glaring omission — any recommendation or suggestion that administrators test for toxic polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) contamination.

The indoor air quality app, and the related IAQ “Tools for Schools Action Kit,” provide guidance on an incredibly wide range of potential IAQ issues, including chemical contaminants such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from paints; microbiological issues such as mold; building material issues such as asbestos; outdoor air pollutants from vehicle emissions and industrial sites; and naturally-occurring contaminants such as radon. Indeed, this list only scratches the surface of the various potential air quality issues that are discussed.

The app provides links to resources about various contaminants, as well as checklists to guide school officials when considering renovations, dealing with waste management, handling building maintenance and numerous other situations. EPA is to be commended for the wide range of topics covered and the easy use of the app, even for people who are not tech savvy.

App Overlooks Critical School Issue — PCBs

However, missing from the app appears to be any significant discussion of one of the recently emerging significant indoor air quality issues that schools face — PCB contamination from building materials. The app information recommends beginning an evaluation of IAQ issues with various walkthrough checklists to determine if potential IAQ issues exist at your school.

These include a Renovation and Repair Checklist, which would be particularly relevant in addressing PCB issues. That list includes:

- Checking paint for lead

- Consulting an asbestos professional to inspect for asbestos

- Evaluating work areas for signs of mold

- Allowing time for off-gassing of new materials in the space before it is occupied

However, there is no mention in this checklist (or any other that I could find) for testing for PCBs.

The app itself omits PCBs from its recommended evaluations and checklists. It does not appear to have any specific reference to PCBs as even a potential issue, aside from the discussion in the “Energy Efficiency” section of the Action Kit.

This omission is not due to a lack of knowledge at EPA of the prevalence of PCB contamination in schools. The reason for this omission is entirely unclear.

EPA Offers Guidance for PCB Contamination in Other Materials

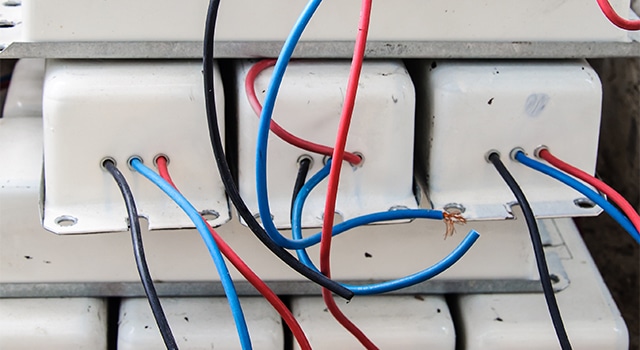

Indeed, the EPA publishes information for schools and other buildings dealing with PCBs in building materials. The EPA also publishes indoor air quality standards for PCBs in schools and has sections on its website addressing PCBs in various building materials such as caulking and light ballasts. Yet, testing for these potential issues does not appear in its recently released IAQ app.

To be fair, there is a substantive discussion of PCBs on page 37 of the “Energy Savings Plus Health” section of the Action Kit. In this section, the EPA discusses how to assess and mitigate PCB issues — at least as related to caulking and fluorescent light fixtures.

Removing PCBs from School is Expensive

The potential costs associated with remediating building materials in schools that contain PCBs can be extraordinarily high. Schools across the country — Massachusetts, Washington state, Connecticut and elsewhere throughout the U.S. are dealing with this expensive issue in increasing numbers in recent years.

Accordingly, school administrators may have an understandable hesitation to open the can of worms by testing for PCBs voluntarily. This is one potential explanation for EPA’s omission of that suggestion in the app.

But ignoring a potential hazard does not make it disappear. The omission may have been merely an oversight by the EPA, rather than an implicit encouragement of adoption of the ostrich approach by school districts. As the app gains traction and is revised in future versions, hopefully this omission will be corrected.

In the meantime, as the EPA has recognized elsewhere, testing for and properly addressing PCB contamination issues are important steps for schools to take. These issues have potentially high costs — costs that rightfully should be borne by the manufacturer of PCBs, Monsanto — not by local school districts and taxpayers.

Todd Ommen

Todd Ommen