Train Derailments Involve Crude Oil and Explosive Fires

Less than a week before the deadly Amtrak passenger train derailment in May 2015, six tank cars of a freight train carrying crude oil derailed and exploded into flames in rural North Dakota. The derailed train burned for more than 24 hours and forced the evacuation of approximately 40 nearby residents.

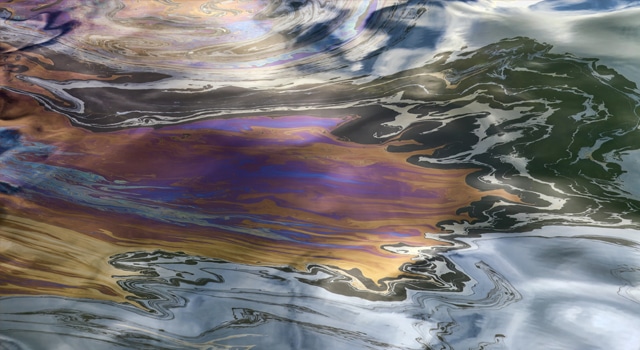

In March 2015, almost a fifth of a train — 21 out of 105 cars — carrying Bakken formation crude oil left the track and caught fire in a rural area near Galena, Illinois. The tank cars temporarily survived the train derailment intact, but the heat built up so much pressure within them that they were ignited by a spark. The crude oil train blew up and became engulfed in a flaming pool of oil that leaked from damaged cars, sending giant fireballs hundreds of feet into the sky.

In February 2015, a 109 car freight train carrying 3.1 million gallons of crude oil from the Bakken Shale of North Dakota derailed in Powellton Hollow, West Virginia. Twenty-seven of the rail cars went off the tracks near the Kanawha River and 19 caught fire. The derailed train burned for days and forced the evacuation of more than 100 residents nearby. Some of the oil spilled into the river.

Threat of Future Train Derailments

Fortunately, no one died during these incidents. However, as we saw in the disaster of the oil train derailment in 2013 in Lac-Mégantic, Ontario, that is not always the case. In the Ontario derailment, 47 people were killed and more than 30 buildings were destroyed by the explosion and conflagration that ensued. These train wrecks can be lethal, and the damage to property and the environment can be expensive to clean up and repair.

Last July, a U.S. Department of Transportation report projected that during the next decade there would be an average of 10 derailments per year of crude oil trains. If the train derailment occurs in one of the densely populated cities through which these trains routinely travel, it could kill dozens if not hundreds of people and cost billions of dollars in property and environmental damage.

Dramatic Rise in Crude Oil Transportation

The volume of crude oil transported by rail has risen dramatically over the last decade, prompted mostly by the oil shale boom in North Dakota and Montana. Growth in transport of oil by rail has soared from the 9,500 railcar-loads shipped in 2008 to 500,000 carloads last year.

That means that about 10 percent of the oil moving through the United States is now carried by rail. This year, railways are expected to transport nearly 900,000 carloads of oil and ethanol in tankers, with each car holding 30,000 gallons of fuel.

“Soda Can” for Crude Oil Rail Tank Cars

One possible source of the incendiary rail disaster problem is that the majority of the oil is being transported in tens of thousands of DOT-111 tank cars. These are called “soda cans” by critics because they are susceptible to being easily punctured and crushed during a derailment.

Ominously, a 1991 National Transportation Safety Board report found that the DOT-111 tank car had a “design flaw that almost guarantees the car will tear open in an accident, potentially spilling cargo that could catch fire, explode or contaminate the environment.” However, despite knowing the danger, the agency did not mandate new tank cars with thicker and safer shells.

According to the NTSB, when a tank car is exposed to heat from a pool-type fire, the internal pressure increases, and the tank may rupture if a pressure relief device cannot sufficiently relieve internal pressure. The resulting tear in the shell releases built-up pressure, ejecting vapor and liquid which can ignite in a violent fireball.

New Federal Regulations

On May 1, 2015, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) unveiled new regulations to enhance the safety of transporting oil by rail. Among other constraints, the regulations require that new and retrofitted tank cars must have thermal insulation and pressure relief valves to protect against heat and flames.

The regulations will phase out older model tank cars that have been deemed unsafe and replace them with a “new generation” of more robust cars, the DOT-117s, built to stronger specifications, including thicker steel shells.

Unfortunately though, the DOT retained a 20-year-old standard for the time duration during which a tank car should survive a pool-type fire. In addition, the new regulations do not focus on reducing the trapped volatile gases within the rail cars.

New Federal Regulations Criticized As Inadequate

Although the new rules are seemingly a move in the right direction, critics say they do not provide adequate protection against fire and heat, factors that cause rail cars to explode. Instead of imposing a tougher regulation, as some sought, the DOT kept in place the rule that tank cars must be able to survive being engulfed in a pool-type fire for a minimum of 100 minutes without failing.

However, according to experts, that older regulation was written for liquefied petroleum gas, not crude oil. In addition, this position ignored the 800-minute threshold recommendation of the Association of American Railroads, which represents the railroad industry.

Moreover, as fire fighters warn, if a fiery derailment were to occur in a densely populated area, it would challenge the combined manpower of several fire departments. More threshold time is necessary.

Some critics have argued that the new regulations focus too much on the long-overdue strengthening of tank cars that carry the oil.

In addition, they should focus on regulating the one thing that could immediately reduce the risk of a deadly disaster: reduction of volatile gases that the oil contains when it comes out of the ground, before the crude oil is loaded into rail tankers.

These gases include propane and butane. Thus, it’s no surprise that a spark can ignite these gases in the circumstances of a train derailment and punctured rail car.

No doubt because the oil industry profits from the sale of these gases, after the rail cars reach the end of the line, possible regulation was thwarted by stiff lobbying efforts by the industry.

Unfortunately, the new regulations do not appear to be adequate to reduce substantially or eliminate the risk of another Lac-Mégantic-type train disaster. Should injury to persons or property strike again in such a terrible manner, Weitz & Luxenberg has the knowledge, resources and skills to assist. Contact us so we can help.

Curt Marshall

Curt Marshall